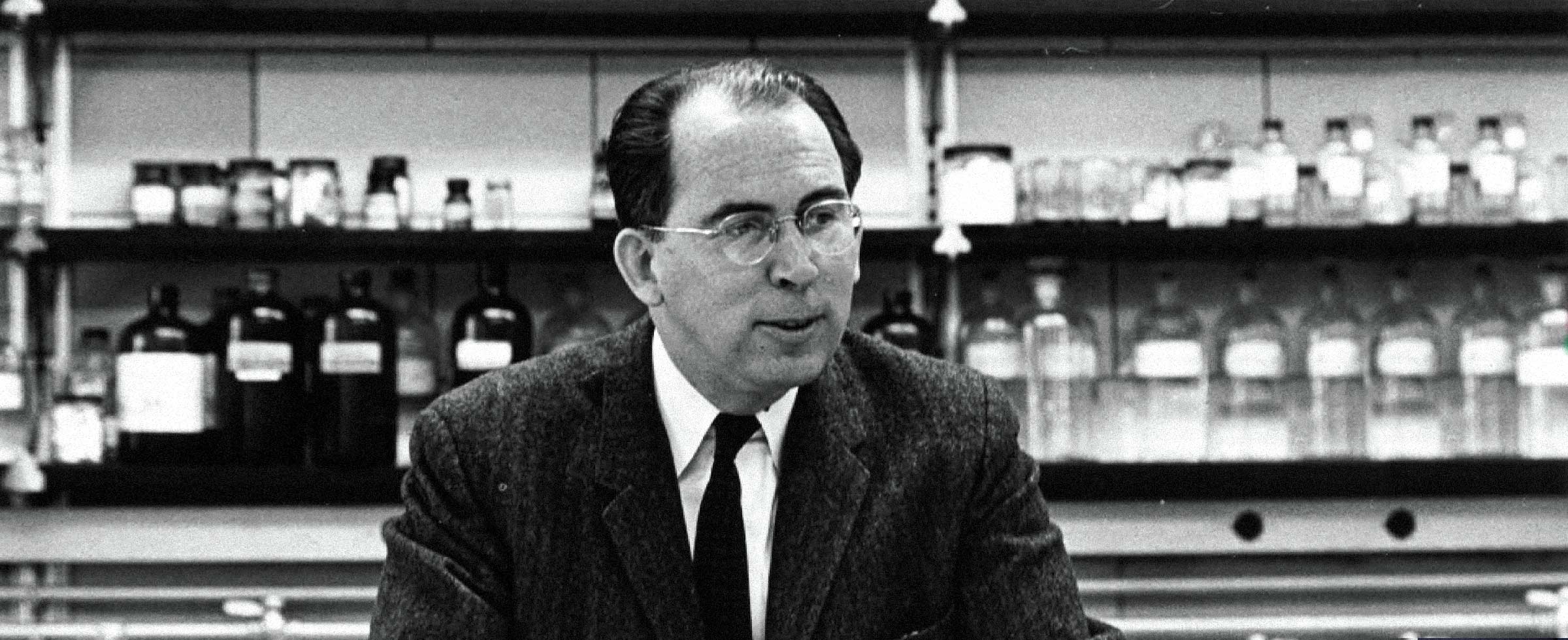

Not everyone is fortunate enough to spend a career working at something they love, far fewer completely transform an entire field of study, and fewer still dedicate the wealth they’ve gained from these pursuits to benefit future generations. Pittsburgh Foundation donor Dr. Robert L. Feller passed across all these thresholds.

A world-renowned art conservator and highly accomplished artist, Dr. Feller, who died in August at 98, invented new methods and chemical processes that revolutionized the field, and he wrote hundreds of pieces about preserving and restoring artworks. He was also a philanthropist who worked closely with The Pittsburgh Foundation over the last 20 years, establishing several planned gifts with the goal of funding organizations promoting early childhood literacy, protecting the riverfronts and other natural resources, and advancing the study of human aging.

“Bob was surprised at the path that his life took,” said Stephen Paschall, an estate attorney who represented Dr. Feller in the last 15 years of his life. “There are very few people who, in their lives, essentially create an entire field of study … He was grateful for the opportunities he had had and wanted to make certain that others could also have opportunities … to develop in a way that they could contribute to society.”

From Artist to Scientist

Born in Linden, N.J., in 1919, Feller took to art as a teen, creating charcoal portraits and drawings inspired by pictures in magazines. As an undergraduate at Dartmouth College, he produced a series of illustrations for the cover of a student humor publication, and began working in watercolors, which remained a lifelong avocation. But despite the gallery-worthy quality of many of his paintings, it was his scientific pursuits that put him on the map.

Following service in the Navy during World War II, Feller completed his graduate studies in chemistry at Rutgers University, where his artistic background sparked an interest in the field of “color science.” Upon graduating in 1950, he attracted the attention of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, which was working in partnership with The National Gallery of Art to establish a research lab at the Mellon Institute focused on finding new ways to conserve works of art. Recruited to head up the effort, Feller soon established himself as an expert in the evaluation of paints, papers and varnishes.

According to retired art conservator John Bogaard, whom Feller hired as a freshly minted Carnegie Mellon University chemist in 1978, this was at a time when acrylics and other man-made materials were being introduced into the field. “But no one knew how they would hold up, what the problems would be.”

In time, Feller’s lab research led to more than 100 publications, including three books. The first, On Picture Varnishes and Their Solvents, published in 1959, has since become “a classic in the field” according to Bogaard, and “is on the bookshelf of probably every painting conservator around the world.” During the 1960s, Feller was called on to apply his expertise to such projects as the restoration of paintings damaged in a flood in Florence. He also helped the National Gallery detect fakes. In the 1970s, he expanded his focus to paper deterioration and the study of accelerated aging in artwork. In 2011, his work was recognized by the American Institute of Conservation with a Lifetime Achievement Award.

Love and Legacy

Beyond professional success, Feller’s career led to him meeting his wife, the highly accomplished color scientist Ruth Johnston-Feller, then working at Pittsburgh Paints. Joining his lab on an advisory basis, her work on the standardization of colors complemented Feller’s professional strengths as perfectly as her personality overlaid his. The result was a decades-long marriage. In 1988, the pair retired from their respective jobs and built a house in Deep Creek, Md. Ruth’s deteriorating health forced them to return to Pittsburgh in the late 1990s and she died in 2000.

It was during this time that Feller became active in his personal philanthropy. He established several charitable remainder unit trusts (CRUTs), naming individuals to receive annual distributions through their lifetimes, and then the balances are contributed to funds supporting Feller’s designated areas of interest. In addition, he named the Foundation as the largest beneficiary of his estate. In all, approximately $12 million will go to the funds he established.

The CRUTs honor important people in his life — from fellow art conservators to family members. The Maura Cornman Fund, for example, is named for a colleague at the University of Missouri and will be used to conserve objects in the Museum of Art and Archaeology’s collections. The Luetta Johnston Scholarship Fund, named for Ruth’s mother, supports students at a high school in Polo, Ind., where she lived and taught. Two other scholarships benefiting graduating seniors at his New Jersey high school were created to honor his parents, an uncle and an aunt.

“He was an extraordinarily intelligent, attentive scientist, still publishing into his 80s,” remembered Paschall. “But at the same time, he was one of the most unassuming people you could run into.”

Foundation Director of Donor Services, Lindsay Aroesty, who met Feller when she joined the Foundation in 2010, recalled him similarly. “His legacy was important to him. He was proud of himself and could talk for hours, but not in an arrogant way. It was all about his amazing career.”

Original story appeared in Forum Quarterly - Fall 2018