Paying it forward

On Sept. 7, 2011, Maggie Elder wrote in her journal, “Today has been a day of 1,000 tears. Today has been a crying day for me, although I’m not sure why… Mom also says those are healing tears and to just let it flow out of me… Tomorrow will be better.”

Maggie, 11, had been diagnosed in July with stage four Ewing’s Sarcoma, a rare bone cancer, and had spent three months shuttling from Ligonier to Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh with her mother and stepfather, Cyndi and Jim McGinnis. Maggie would spend a week at a time in the hospital for treatments and then head home to recover. It was grueling and terrifying. The family turned to Carol May, founder and manager of the Supportive Care Program at Children’s, for guidance through an unthinkable situation.

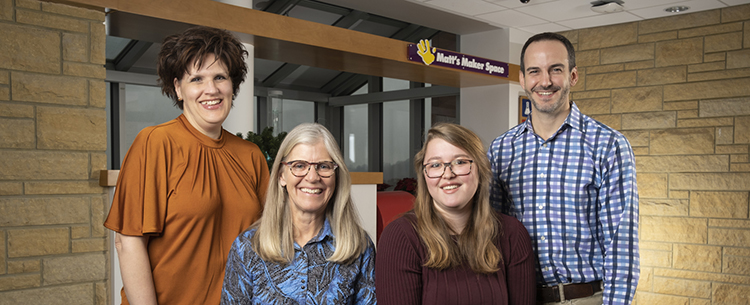

Carol May (far left), RN, MSN, MBA, CHPPN, founded the Supportive Care Program at Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh and manages it with Scott Maurer, MD, who oversees palliative care at the hospital and also sees oncology patients. May and Maurer are pictured here with Maggie Elder's mother, Cyndi McGinnis, and sister, Mackenzie Elder.

The Supportive Care Program – which oversees treatment, provides pain management, guides family members and helps them manage their hopes and fears – became the family’s anchor. May and the team were especially helpful in providing emotional support to Maggie’s 13-year-old sister, Mackenzie, and helped the entire family manage their anguish as Maggie’s illness progressed.

May, who discovered hospice at age 17 when her grandfather died at home, has dedicated her career to helping people die with grace and dignity. She earned three advanced degrees in nursing and management, working in adolescent oncology and running a hospice program in Michigan before returning to Pittsburgh 15 years ago to establish Supportive Care, one of only five such programs based at children’s hospitals in the country.

The young patients and their families are wrapped in a cocoon of care that begins with medical treatment and extends to emotional support for the loved ones of children who do not survive. Program staff are currently following about 1,200 families who have lost children over the past 10 years. The goal is to improve pediatric palliative care.

“The program provides a space to deal with the most horrible thing imaginable,” says May. “We work with families on how to honor and meet their cultural and religious needs, so that their child is comfortable and understands what’s happening.”

For Cyndi McGinnis, the program’s ground-breaking work eased what would have otherwise been unbearable.

“They made it a point to understand what we value most,” she says. “They knew we are a faith-driven family and they honored that. They knew we wanted to get Maggie home and they made it happen. Maggie got to spend five weeks at home on hospice care before she died.”

Their care for Maggie continued as she transitioned to home hospice.

|

“Once we got her home, pain management was a big piece,” McGinnis says. “Carol was on the phone with us every day helping to adjust medications because managing pain in children is completely different than for adults. She drove 70 miles each way to visit with Maggie. They even managed to get us out on a Make-a-Wish family ski trip a month before Maggie died.”

While families say the value of Supportive Care services is immeasurable, only a fraction of the costs – May estimates 15 percent – are reimbursable under health insurance. The program relies on funding from hospital administrators who believe in its mission, philanthropies that see the benefit, and communities like Maggie’s, who organize fundraising events.

After Maggie’s death in February 2012, the family used money raised from a series of road races and wristband sales to establish the Miracles from Maggie Fund at The Community Foundation of Westmoreland County. To date, $130,500 has been donated, including $100,000 from the CFWC fund, to establish an endowment that now provides a permanent funding source for the program that meant so much to Maggie and her family.

That endowment helps to fund research into new palliative- and bereavement-care methods to improve quality of life for children facing life-threatening medical conditions. The research is meant to guide other hospitals in establishing their own supportive care initiatives. Under the direction of Dr. Scott Maurer, an oncologist who oversees palliative care, the program publishes its research findings in medical journals and presents at national and international meetings. The researchers’ biggest initiative to date is the Pediatric Patient Reported Outcomes study, a project involving care teams and families at hospitals and universities in five cities.

“To study symptom control and quality of life in children who are undergoing cancer-related therapy, we’ve developed a tool to allow children as young as seven to report their own symptoms, including those as complex as depression,” says Maurer. “The goal is to give children a voice by asking them directly instead of going through parents or caregivers.”

The team is also studying the intersection of spirituality and medicine and how spiritual distress, a common occurrence in life-threatening medical crises, affects overall quality of life. They also teach pediatric residents and medical students how to communicate with families and listen compassionately when sharing bad news. Cyndi McGinnis and other parents who have benefited from Supportive Care share their experiences with second-year residents. Mackenzie Elder, now 21, and pursuing her bachelor’s degree and soon her master’s in social work at the University of Pittsburgh, speaks at the program’s annual memorial service for families. She also serves as a counselor at the program’s overnight camp for bereaved siblings.

The pay-it-forward volunteerism gives comfort to their family, says McGinnis.

She remembers the motto that Maggie created to help her through the journey: ‘Faith can crush fear.’ She really left a blueprint for how to live. It would just make her heart so happy that we’re able to continue helping other people in her memory.”

# # #

To learn more about Maggie and her family and their charities, please visit http://miraclesfrommaggie.org. More information about the Supportive Care Program is available at http://www.chp.edu/our-services/supportive-care.

Give to miracles from maggie fund

Gifts to the fund support the Supportive Care department at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh.

Original story appeared in the Forum Quarterly Spring 2019.