Ripples of hope in the wake of addiction

SPENSER FLOWERS, a witty 20-year-old with a loving heart, died of an accidental heroin overdose at his parents’ home on New Year’s Day. While his addiction was not a secret from his family, who had helped him find the rehabilitation he sought, the timing was excruciating: hours before his death, he had spent time researching a treatment center he could enter to try again.

“We ran out of time,” says his mother, Tina Flowers of Allison Park.

Spenser was the victim of a rising epidemic afflicting the nation and, disproportionately, the Pittsburgh region. The Centers for Disease Control reports that in 2015, 52,000 Americans died from accidental overdose, mostly from opioids — a 20 percent increase from 2014. By contrast, the 613 deaths reported in Allegheny County in 2016 represented a 62 percent spike over the previous year’s numbers.

Flowers shared similarities with the majority of other recent local opioid victims: he was white and he was male. And like 58 percent of fatalities in Allegheny County, he overdosed before reaching his 35th birthday. Drug overdose deaths have skyrocketed among teens and young adults in the United States, with rates tripling or quadrupling in one out of every three states, according to a report from the Trust for America’s Health.

A generation is at risk.

Tina, her husband, Chris, and their older son, Sam, have created a positive way to remember Spenser and save others. In March, they established two funds at The Pittsburgh Foundation: a scholarship, with assistance from financial advisor Lou D’Angelo at Raymond James, for members of Spenser’s youth group at St. Paul’s United Methodist Church in Allison Park, and Spenser’s Voice, which funds organizations working to curb the drug epidemic in young adults. Friends and relatives have contributed to both efforts.

“I knew the day he died that we would want to establish the scholarship fund,” Tina says.

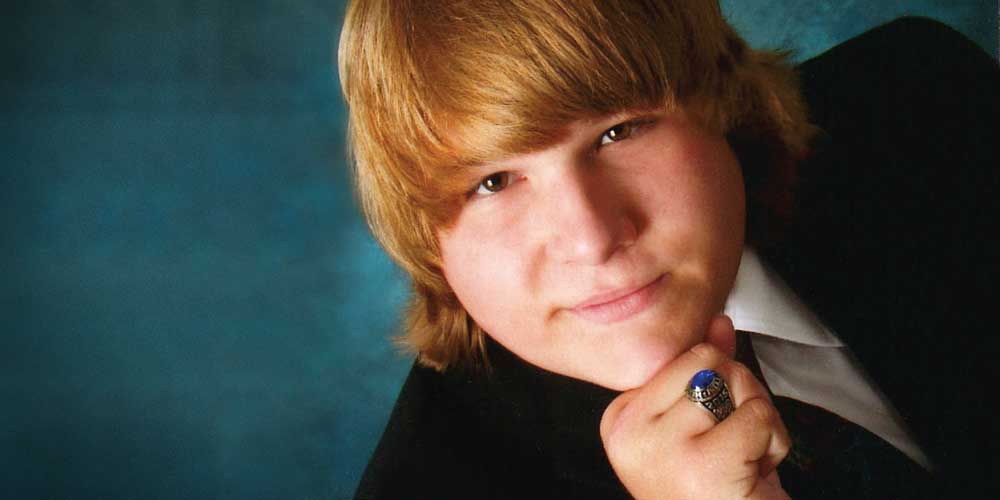

Spenser Flowers, pictured above in his Class of 2015 Hampton High School graduation photo, was 20 years old when he died of an opioid overdose.

While attending Hampton High School, Spenser had been an active participant in St. Paul’s youth activities, volunteering for five summer work camps. “He always said he was at his best at church and around those friends,” his mother recalls. She remembers her son as “a normal, suburban young man,” one who was crowned 2015 homecoming king his senior year, loved Harry Potter novels and silly hats, and was “always mischievous.” After briefly attending Temple University, he returned home, struggling with anxiety and depression. Sixteen months later, he was dead.

As an attorney and community volunteer, Tina realized that the city desperately needed strategies to prevent other young people from meeting Spenser’s fate. That’s the purpose of Spenser’s Voice, which provides funding to implement three community strategies.

The first addresses Narcan (naloxone), now widely used by individuals and emergency responders to revive overdose victims. But, as the Flowers family learned, many suburban police officers don’t carry the drug and have yet to be trained to administer it. When Spenser overdosed on Dec. 26, six days before his death, the family had the antidote on hand and revived him, but the officers who arrived to answer their 911 call had not received formal instruction in using it. A comprehensive regional training plan is needed.

The Flowers also see a need for treatment facilities with special programs for 18- to 25-year-olds. Many detox centers are treating alcohol abuse or other drug disorders in settings that overlook the emotional needs of younger patients. The family also supports ways for families to seek emergency treatment for a loved one when the individual refuses treatment for substance abuse. Unlike other states, Pennsylvania currently allows for involuntary commitment of those diagnosed with a mental illness, but there is not a parallel law to provide involuntary treatment for substance abuse. Legislation introduced in February by State Sen. Jay Costa (D-Pittsburgh) addresses the issue.

Finally, the family is working to combat the stigma of addiction among families struggling to help their loved ones.

“I see a strong parallel with the AIDS epidemic,” Tina says. “We’ve gotten over that — we now know it is a disease that can be treated. Individuals and families should not have to feel so alone” in combating public perceptions about substance abuse. She has addressed church, community and school groups about her family’s experience and will continue to be involved in advocacy efforts.

“We are not going to criminalize this away,” she says of the efforts. “We’ll never give up. We must keep trying.”

Original story appeared in Forum Quarterly - Summer 2017