Dr. Yinka Aganga-Williams: Twenty years of creating refuge for immigrants in Pittsburgh

Dr. Yinka Aganga-Williams first came to Pittsburgh in 2000 to settle one of her daughters at Duquesne University. Twenty-one years later, she’s still here. It all started after Mass at St. Benedict the Moor Church in the Hill District, where Fr. Carmen D’Amico was pastor. D’Amico invited her to a meeting about helping South Sudanese young men who had spent most of their lives in refugee camps before being resettled in Pittsburgh. Aganga-Williams has lived in 18 African countries, where she worked with governments on youth and women’s policies. She possesses the cultural sensitivity to help these young men feel at home. In 2004, Pastor D’Amico and Aganga-Williams formalized their work with refugees by co-founding Acculturation for Justice, Access & Peace Outreach (AJAPO), which helps as many as 300 immigrant and refugee families a year make Pittsburgh their home. AJAPO is now governed by an eight-member board of trustees and is an affiliate of the Ethiopian Community Development Council, one of nine national resettlement agencies in the U.S. Over the years, The Pittsburgh Foundation has awarded grants totaling $310,500 to AJAPO. Aganga-Williams discusses AJAPO’s origins and why she believes that no human beings, no matter how far from home, should be considered lost.

IN THE BEGINNING, Catholic Charities partnered with St. Benedict the Moor, a predominantly African American Catholic parish. We began working with South Sudanese young men who were from 3 to 6 years old when their parents sent them to Ethiopia and Kenya to keep safe. When they arrived in Pittsburgh in 2001, they became known as the Lost Boys of Sudan. I had to reassure them several times that they were not lost boys but human beings just like all of us and must never accept that they are lost.

By 2002, there were 40 of them; the oldest was 26. The federal government provides special funding for the first 90 days of resettlement, but we work with them far longer as that is what’s needed for people to find their feet. We assist them with social services coordination and job placements. Five years from when they arrive, they are eligible to become citizens, and that is why AJAPO also provides legal immigration services to see them through.

In 2006, AJAPO was asked by the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services to help 40 families resettle, which turned out to be over 200 families. These types of surprises show why governments cannot work in isolation — we need philanthropy to bridge the gap.

When the last administration cut back on refugee admissions to the U.S., some resettlement agencies had to shut down. Foundation funding kept us open. We are doing more for those who are here. When people are displaced for over 20 years, they need more to grow and become citizens.

We are working with people who came from trauma, looking for freedom in our country, and now they are dealing with COVID trauma. With COVID, all our clients lost their jobs and everything that goes along with that. But, to be honest, I think we have every reason to give thanks, as COVID spread was very low among this population. Due to early intervention, they have all gone back to work, thanks to Allegheny County and city government, philanthropy and community leaders.

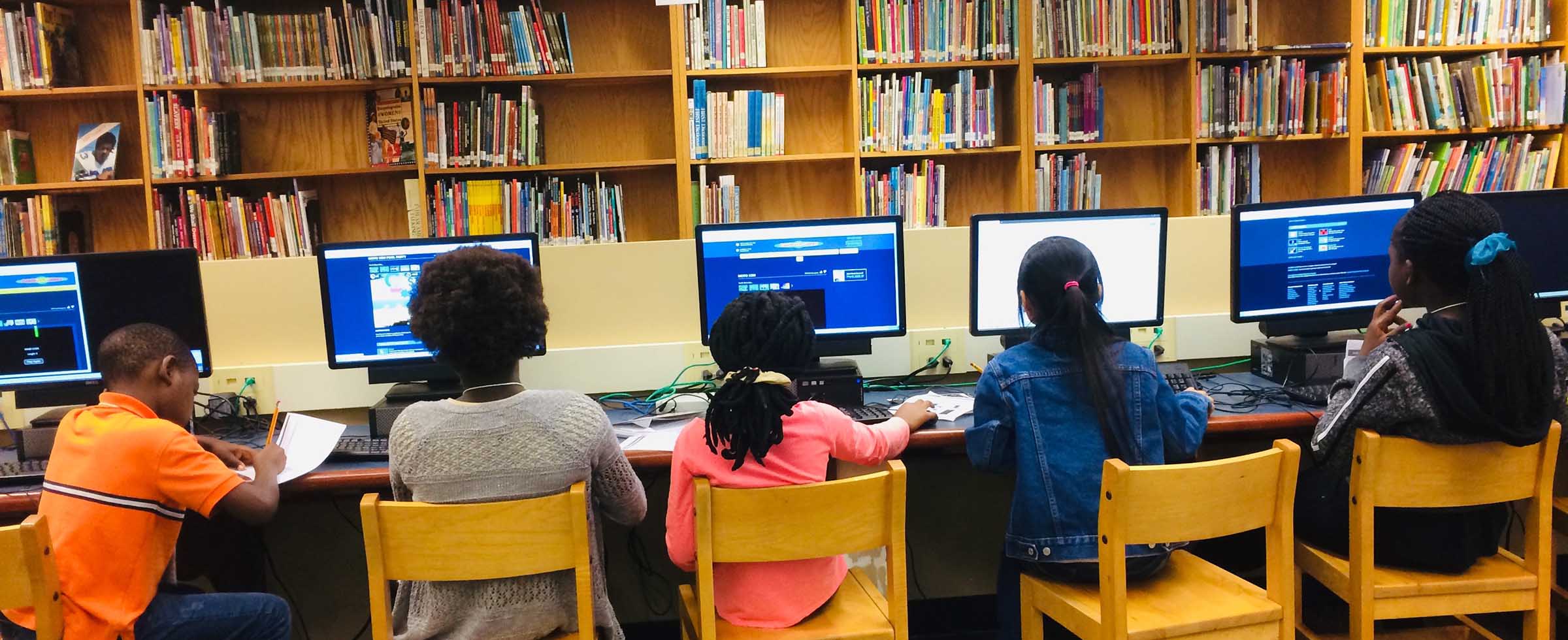

What worries me now is education for refugee children. The government requires us to enroll them in school within 30 days of arrival. But who is bridging that gap between a child coming in as a refugee and the mainstream children and their teachers? I would truly like to see a program that provides our kids with orientation and prepares them for the school system here.

Roughly 80% of our refugee parents have little education or are pre-literate, meaning they cannot read or write in their own languages. Who is helping their kids now that they cannot be in class? The stress placed on these kids means that they cannot get the education they should be getting. This is a matter of injustice and opportunity. We cannot just move these kids up a grade based on their age.

For refugee kids, education is a priority, and it is important to help those who complete high school to access future career and college education planning. Parents may not realize how much debt they are accumulating for their kids to attend college, so we can easily create poverty out of ignorance. If we can guide them toward community colleges and trade schools, it greatly reduces future poverty in families resulting from school loans. I want the world to hear this, and I want the world to help. It’s a question of leadership, of how we help children academically but also with good character and good citizenship so they know what it takes to become contributors. We will all be happier when that happens.

Original story appeared in the Forum Quarterly Spring 2021.