Beyond the wealth facade

WHEN RAYMOND SCHUBART SUCKLING DIED IN 2014 AT 93, he was already one of Sewickley’s most celebrated philanthropists.

In 1993, he established a Pittsburgh Foundation fund in honor of his parents with a gift of $6,000 to the community. By the time of his death two decades later, that initial gift had been followed by $664,000 to the fund, which dispersed $345,000 to various charities and institutions in Sewickley over the years.

His donations had been a generous and impressive show of community spirit by a quiet and unassuming retired engineer who never married and had no children of his own, but who loved helping the less fortunate in the Sewickley area.

That was Raymond Suckling’s mission until his last breath. If his generosity had stopped there, all of those who benefited from his largesse in and around Sewickley would’ve celebrated him into perpetuity. But as it turned out, that gift of philanthropy was the raindrop on an ocean wave.

In January 2018, four years after his death, The Pittsburgh Foundation announced that it was the recipient of a $37 million bequest from the Suckling estate. For the Foundation, it was one of the largest donations in its history — second only to the $50 million Charles E. Kaufman Fund.

Suckling’s gift was a stunning gesture of philanthropy from a man who gave no thought to taking credit before his death.

The bequest specifically earmarked two annual $500,000 grants to be given to two institutions close to Mr. Suckling’s heart — the Sewickley Public Library and the Sewickley Valley Hospital Foundation. While both institutions are still in the planning stage of determining how the significant revenue will be used, the heads of both organizations announced broad directions at a press conference in January. The area of focus for the hospital system, said President and CEO Norman Mitry, is to invest in an enhanced clinical training program for nurses and patient care associates. For the library, the revenue stream will greatly reduce pressure each year to raise funding for existing services and, said Executive Director Carolyn Toth, “increase the library’s vitality in the digital age … by offering programming and physical spaces attractive to children and teens.”

The Foundation also was named as a beneficiary at a fortuitous point in its history: At about the time of Suckling’s death, the Board and staff had committed to a new organizing principle, 100 Percent Pittsburgh, which dedicates about 60 percent of discretionary grant resources to creating new opportunities for the 30 percent of Pittsburgh-area residents left out of the revitalized economy. Suckling’s directive to the Foundation matched up exactly with the 100 Percent Pittsburgh agenda: Additional grants of about $500,000 will be distributed each year to agencies and programs that benefit people living in poverty in and around Sewickley.

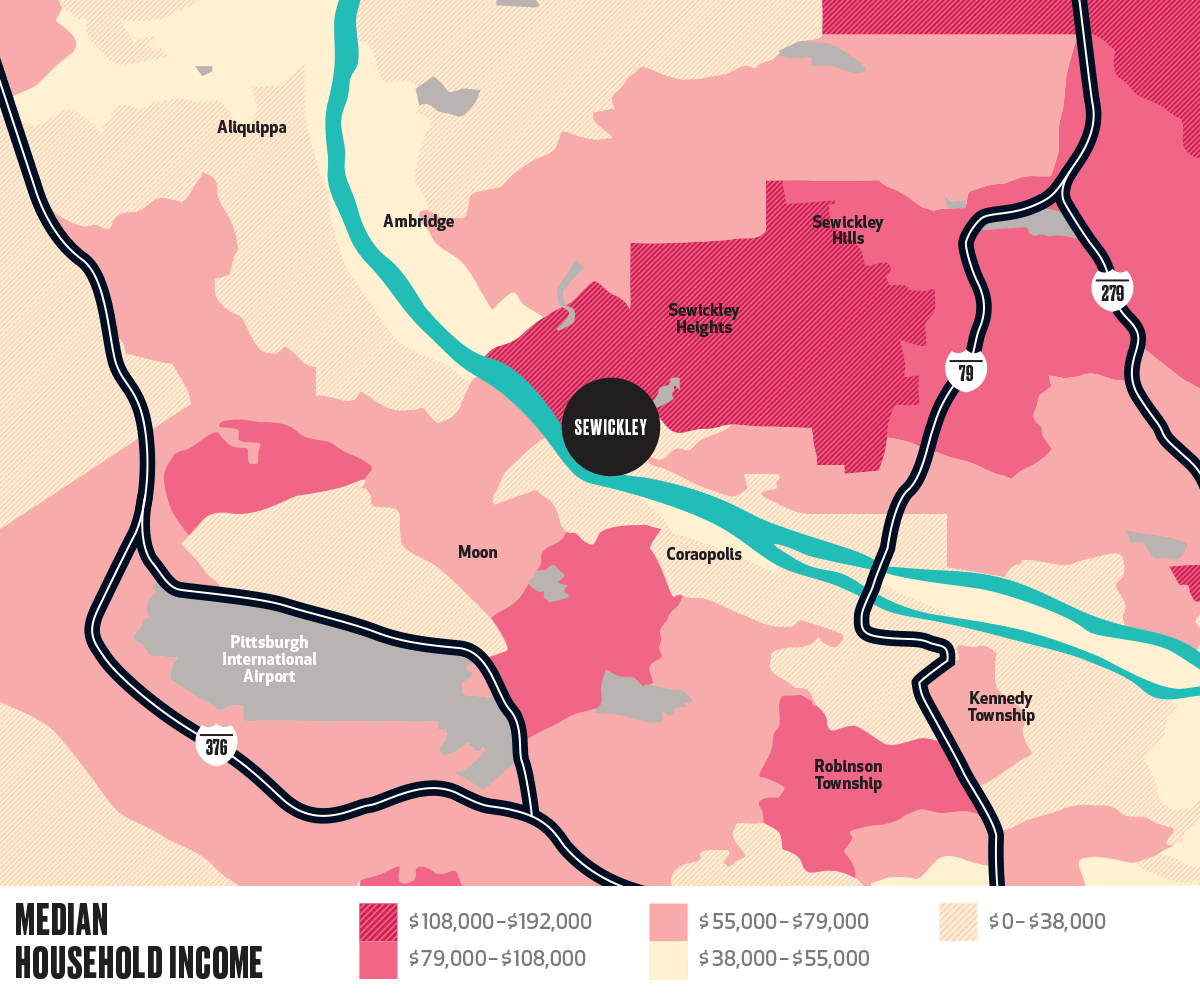

Many only know Sewickley through surface views: a bucolic village with a boutique business district, and in the Heights, fabulous estates carved out across rolling hills. From those perspectives, the idea of hundreds of thousands of dollars flowing into the area each year to help people get access to a vibrant economy is oxymoronic — even ridiculous, given needs elsewhere. Yet Suckling knew that, beyond the façade of “the good life” in Sewickley proper, well beyond the neighborhood in which he was born and raised, there has been economic deprivation for decades.

“We know a lot about poverty in Pittsburgh,” says Jeanne Pearlman, the Foundation’s senior vice president of Program and Policy. “And over the past three years, we’ve begun looking at pockets of poverty outside the Pittsburgh area. Having this fund arrive on our doorstep has allowed us to go even further into communities that people might not suspect are really hurting. We’re following the donor’s lead on this.”

The Sewickley Valley YMCA is among the first local institutions working with vulnerable populations in Sewickley and the surrounding area to receive funding from the Foundation to help finance ongoing operations aimed at helping those in need.

“A lot of people think of Sewickley as a solution in search of a problem,” says Sewickley Valley YMCA CEO Trish Hooper. “They have this image that everyone here is

wealthy. That’s not the case. The image of uniform wealth tends to make problems worse. The image masks some of the challenges that struggling working families have.”

The YMCA received a one-year, $40,000 grant to support scholarships for low-income children attending its 10-week Summer Day Camp in 2018. The services offered run the gamut from state-licensed child care, mentoring for youths in the Teen Center, swimming lessons, including free lessons for children living with Autism Spectrum Disorder, meals, and access to health and wellness programs.

In 2017, the YMCA issued 183 scholarships and $85,000 in assistance for the Summer Day Camp. “We had $45,000 [for scholarships] and the Suckling grant provided $40,000,” Hooper says. “This year’s assistance amount is expected to be about $100,000, which would cover 204 children. The Suckling grant will help us fund the leftover portion.”

A broader view of the YMCA’s work validates the high numbers of those in need. Last year, the facility provided $433,000 in membership scholarships, summer camp experiences and child care to 1,450 economically disadvantaged individuals and families who use its various programs and services year-round.

“There’s a mindfulness, kindness and compassion all working together in this community to help every kid reach full potential,” says Floyd Faulkner, the Quaker Valley School District’s community youth worker who works out of the Sewickley Valley YMCA.

“We have 15 to 20 percent of students receiving free and reduced-price lunch in this district,” Faulkner says. “But we have to remember that all kids are at risk of making choices and decisions that can jeopardize their futures and their goals — not just kids considered at-risk.”

Faulkner, who likes to feel the pulse of the community by getting out and about as much as possible, works hard to build relationships with all young people, regardless of socio-economic level.

“Overcoming the assumption in the community that I’m here just to work with a specific group of kids is the biggest challenge,” he says. “There’s still an element of pride. Not everyone who needs help will ask for it. We want to positively impact all children, but I think about the kids I can’t reach.”

Faulkner’s job is to build relationships with the latchkey children, those hanging out at the library and those living in working-class neighborhoods, so he can help identify resources they may need. It is a job that reflects the values and concerns of Suckling and the ongoing mission the late philanthropist wanted his bequest to fund.

“We were already thinking conceptually along these lines,” says Pearlman, reflecting on the work going on in Sewickley and underserved communities outside of Pittsburgh, “but Mr. Suckling opened the door and shined a light on this issue.”

LESSON LEARNED: Poverty is not constrained by geography, but in wealthier areas of the region, it can be invisible and therefore hard to address. In addition, poverty must be examined as a regional issue, rather than an issue confined to certain neighborhoods in and around the City of Pittsburgh.

Original story appeared in Report to the Community 2017-18