If human services providers in Westmoreland County are exhausted, it’s no wonder. More than 160 government and nonprofit agencies are trying, without formal coordination, to serve 355,000 people who live in urban and rural areas across the massive county.

In the past, providers have banded together informally to harmonize services and solve problems. That began to change last year thanks to findings of a study funded by The Community Foundation of Westmoreland County (CFWC), United Way of Southwestern Pennsylvania and the Westmoreland County Commissioners. The project, which looked at human services providers

operating for five years or more, tapped the expertise of dozens of providers and analyzed how 12 other counties organize human services delivery to improve quality of life for residents.

The report “Improving Human Services in Westmoreland County” recommends that the commissioners create a county human services department and hire a professional to direct it. The report offers evidence of dramatically improved quality of service and efficiency through coordination of providers in Westmoreland, which ranks among the largest dozen Pennsylvania counties by both population and land area. Westmoreland County officials, with funding from CFWC, are searching for a director. The county commissioners hired a consultant in February to lead the search. They’re expected to hire a director this year. Funding from the Richard King Mellon Foundation will support the position.

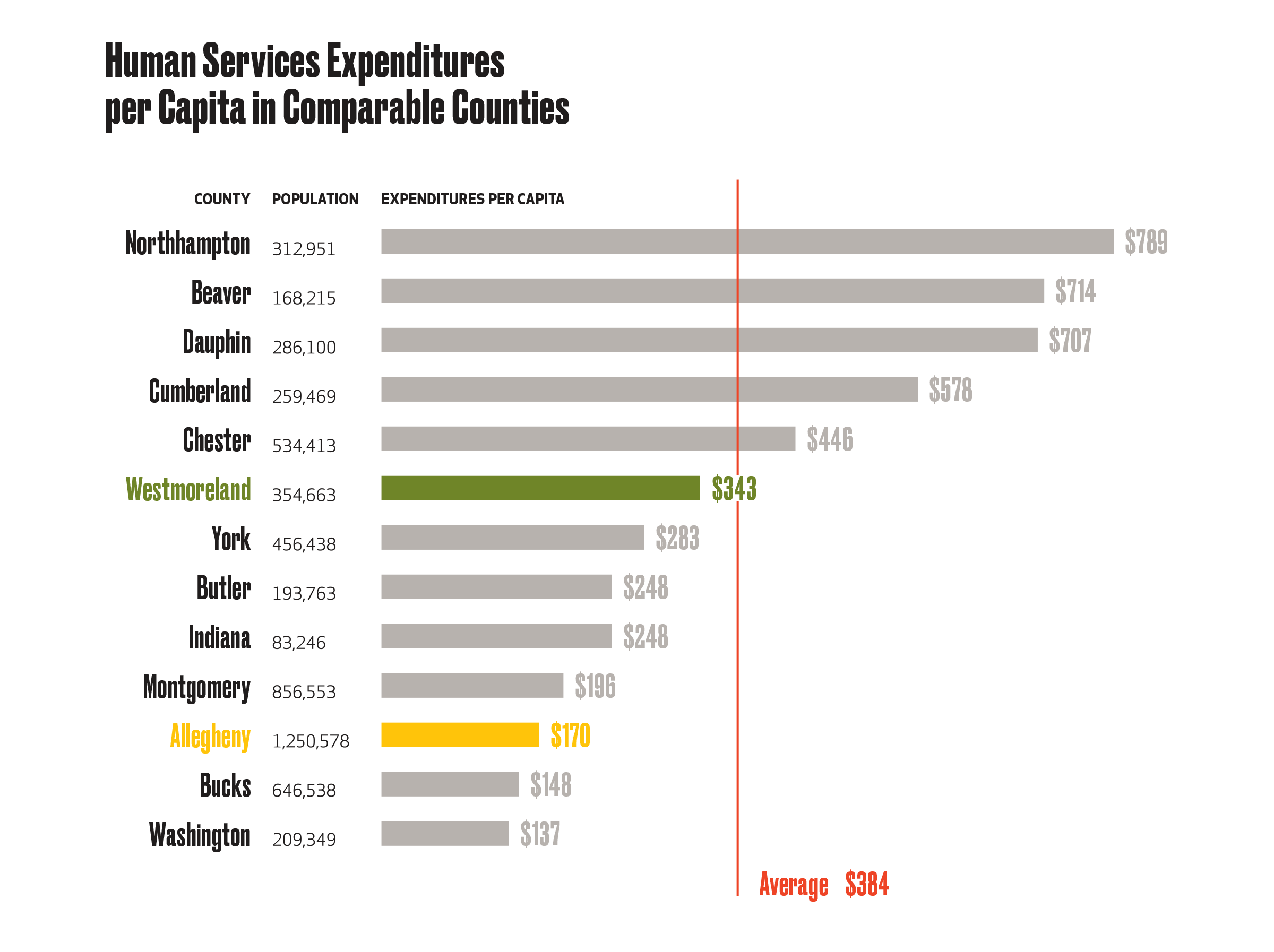

The study found that Westmoreland’s investment in human services is $343 per person per year, double the amount spent by Allegheny County, which has a population of 1.25 million and a nationally recognized human services department.

A coalition of providers is stronger than each provider on its own.

—McCrae Martino, executive director of The Community Foundation of Westmoreland County

As executive director of CFWC, McCrae Martino has been a leader in the movement to incorporate a human services department into county government. Having department status, she says, will better serve the county’s elderly, those with disabilities and other vulnerable populations. In addition, she says, it will serve as a convenor and help provide resources, establish goals and improve data sharing.

“A coalition of providers is stronger than each provider on its own,” says Martino. “A director of human services leading a department will be able to delve deeply into what’s happening in communities, meet with providers to assess needs and help develop solutions.”

Study funders expect that elevating human services to a department will enable development of data sharing systems that will cut red tape and make life easier for people served and providers.

“If a client goes to a housing agency but also needs food assistance or other services, shared data systems can make referrals and eligibility paperwork happen faster and be easier to complete,” says Martino. “That’s a long way off, but it’s just one of the ways that county dollars invested in human services could be spent in a more strategic way and make it easier for clients to get the services they need.”

Service coordination is especially critical in rural areas, such as Westmoreland County, where scarce public transportation can make getting to appointments difficult for low-income residents without cars. In addition, the county’s large size is challenging to providers who drive to clients’ homes.

Jordan Pallitto of The Hill Group, which conducted the study before he became chair of the CFWC Advisory Board, acknowledges the work service providers managed to accomplish without central leadership. “They have done a tremendous job collaborating informally and have managed to innovate even without the critical infrastructure that many other counties have,” he says. “Hats off to the providers, but just imagine what they could do with more structure and coordination.”

Original story appeared in the 2021 Report to the Community. | See archive of print publications.